Through years and decades, the use of technology has become commonplace in K-12 classrooms, including those within the Diocese of Youngstown’s Catholic schools. Amid the use of apps and email to assess student work, communicate with parents and guardians and introduce students to emerging technology, some diocesan teachers and administrators have begun to adopt the use of generative artificial intelligence (AI).

Generative AI is a type of artificial intelligence that creates content, such as text, images, music and other media. Examples of generative AI include tools like ChatGPT for generating text and DALL·E for creating images.

In his message for World Peace Day in 2024, Pope Francis spoke about AI, saying, “Artificial intelligence ought to serve our best human potential and our highest aspirations, not compete with them.” It is with this sentiment in mind that superintendent Dr. Steven Jones supports diocesan Catholic Schools in becoming early adopters of generative AI in the classroom—while ensuring educators are aware of the risks.

Jones explained that the use of generative AI and other technology in the classroom provides several benefits for students, teachers and parents: “The first thing technology does is increase opportunities … for communication with teachers and families, and it gives students new ways to interact with information.”

Jones, who was a teacher before taking on his position as superintendent of Catholic Schools for the Diocese of Youngstown, elaborated on how the use of generative AI and other forms of technology ultimately allow students to engage with research. “At one point, we were limited with physical holdings in places like the library. That’s not true anymore. Technology opens a world of perspective that our students can interact and engage with.”

Many teachers throughout the Diocese of Youngstown share in Jones’ positive outlook on how technology and AI can benefit educational institutions. “In some schools, there are teachers who are using AI in the classroom for editing exercises,” he explained.

He also mentioned that he sees the use of AI potentially making its way into fine arts classrooms. “When I think of AI, I think of it as generating words, essays, articles. It actually can do a lot more than that. Don’t forget about the arts—some students don’t know where to start, and [generative AI] will help them feel the creativity.”

Lane Knore, a business and computer science teacher at Central Catholic High School in Canton, teaches the course Fundamentals of AI, an elective available to students in grades 9-12. The course, which was first offered in 2023, gives students a chance to interact with AI through programming. “We are learning about the use of building AI and programming it. Kids create chatbots and games, including games that can learn, which is where the ‘generative’ part of generative AI comes in,” he said.

Knore said he firmly believes that this type of instruction on the use of AI has helped Central Catholic graduates in the workforce, specifically those in the business, finance and entrepreneurship fields. “We’ve had past graduates come in and talk to different classes, and those graduates have gotten ahead in business because they use AI to their advantage—generating content, generating analyses for different businesses.”

Knore said he plans to integrate AI into his business courses and hopes other teachers will incorporate AI in their classrooms as well. “We have several different programming classes where the thought is to mix AI in. As teachers get more comfortable, I see them working it into their classrooms and using it for instruction.”

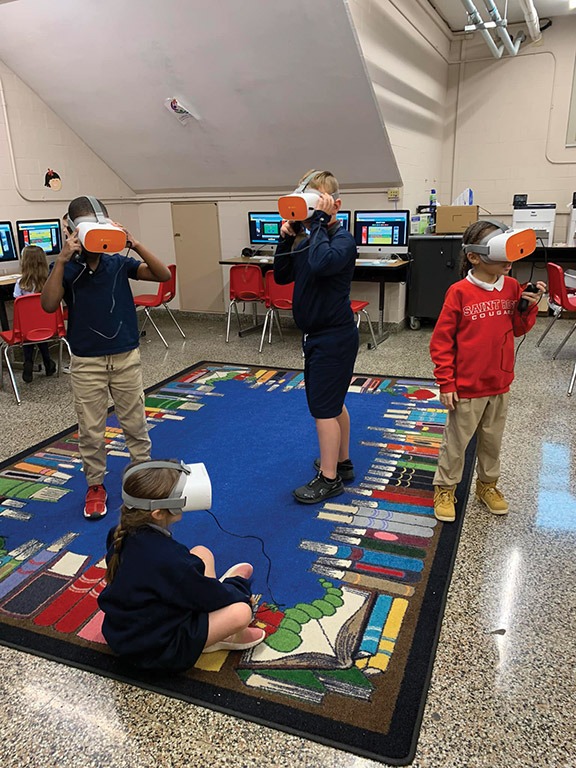

Catholic high schools are not the only educational institutions adopting the use of generative AI. Diocesan elementary and middle schools, including St. Rose Catholic School in Girard and St. Nicholas School in Struthers, have also begun to embrace this emerging technology.

St. Rose principal Anthony Catale said the use of generative AI aligns with St. Rose’s goal to provide a well-rounded education that prepares students for high school. “One of the things we pride ourselves on is that we offer a lot of elective and supplemental classes that are meant to educate the whole child. Financial literacy, 3D printing, coding.”

Catale said he emphasizes the use of AI, not only in elective instruction, but in all classrooms from kindergarten through eighth grade. “In today’s world, we are trying to engage with students with the technology we use on a daily basis. So far, we find that AI is extremely beneficial.”

Regarding the future of AI in elementary schools, Catale said he hopes to add generative AI classes to St. Rose’s selection of elective and supplemental courses. For now, he is pleased with how teachers and staff work AI into their curriculum and mentioned that using AI produces more positive than negative outcomes. “I think the benefits, especially if we teach the kids the right way to use it, certainly outweigh the concerns,” he said.

One of the ways teachers can benefit from using generative AI, he explained, is by consulting with the software to create individualized instruction and assignments. “AI doesn’t replace an educator, but teachers have got the ability to take an informational text and reproduce it at varying Lexile levels for students on different reading levels. That informational text can then reach every kid in the class.” He further emphasized that using AI this way does not replace student-teacher interaction; rather, it enhances it.

David Edelstein, a technology teacher at St. Nicholas School, also shares the belief that technology like generative AI will play a major role in the future of education. Students at St. Nicholas are familiarized with AI in the STEM program, where elementary students use the technology for art and design.

Last spring, eighth-graders Quentin Brown, right, and March Fionini, left, at St. Rose Catholic School in Girard participate in art class. Many fine art students consult AI for “a place to start” on art projects. Photos from St. Rose Catholic School Facebook Page.

Edelstein explained that generative AI allows students to be creative without limits. “One of the projects that students did is build a park inside of a pizza box, and that requires generative AI for facilitation. AI helps students answer, ‘How would I do that? Where would I start?’”

Regarding the use of AI beyond the STEM and design classroom, Edelstein said it depends on the teacher. “There are some teachers who are very technologically curious and interested, and there are some who are not. Some use technology as it’s required, but not more.” Edelstein himself is a proud user of generative AI in his personal and professional life, and he stated that it helps him think about topics and projects in ways he may not have without the use of the technology.

Despite the current and future positive outcomes of using generative AI in the Catholic K-12 classroom, some teachers and staff choose to proceed with strong caution. They have rising concerns about academic dishonesty and misinformation, specifically with technology like ChatGPT.

“I get why teachers are terrified of it. It means you have to grade differently and have a whole new set of considerations when grading, and that’s going to be hard,” said Jones. “When people think about AI and schooling, they see problems, like ChatGPT writing a paper. I do think ChatGPT and other programs are going to raise some challenges for what we mean by ‘this is my work.’”

“I don’t think AI introduces anything new, but in some ways, it has made [academic dishonesty] easier,” he added. “The immediate response from teachers is to do all the writing in class without computer access. In the shorter term, it’s a strategy. In the long term, it’s not a strategy.”

“Part of the problem with generative AI right now is … you really can’t see if the kids are using a service like ChatGPT to answer stuff,” said Knore, who noted the possible solution of checking students’ usage history of ChatGPT to assess if students are using it ethically and responsibly.

While Catale explained he has not experienced pushback from St. Rose faculty and staff on the grounds of potential academic dishonesty, he does understand that changes in technology can be challenging for some. “Sometimes, it’s more the frustration of keeping up with the technology than using it, but AI has the potential to make teachers’ lives easier,” he said.

He also acknowledged teachers’ concerns regarding the accuracy of information produced by AI. “There’s never a full guarantee that all information is accurate. There’s also the risk of students using AI for the wrong reasons. But there are tools to combat that, like AI probability evaluators. A teacher can run text through it, and it will gauge the likelihood of whether generative AI was used,” he explained.

“I am also concerned about bias and misinformation. ChatGPT programs are not perfect, and there are some things it gets wrong,” Edelstein said.

He also recommends that teachers should continue to assign hands-on activities in class, such as in-class writing. To him, choosing to use AI is not black or white, but more of a balance. “AI is a mixed bag, and students still need to learn how things work,” he said, noting that AI is not meant to replace critical thinking skills.

Despite these concerns, all agree that generative AI is not going to go away, and that it is in teachers’ best interest to learn as much as they can about this emerging classroom technology.

”There’s pluses and minuses to any of it,” said Knore. “People are always fighting the change of technology in software. Once they see what they can learn and what they can do with it, maybe they can start using it in their classroom.” He mentioned that his students have used it to create flashcards based on their notes. They have also used it to “talk” to historical figures and learn about them through factually accurate, AI-generated interviews. To Knore, activities like this positively impact students by helping them learn in new ways.

Jones agreed, and like Edelstein, said that generative AI cannot master the larger concept of critical thinking, especially in writing assignments. He said that students must master research and critical thinking skills in order to use generative AI effectively. “It doesn’t matter if you get the right answer if the question is wrong. You can only learn to ask the right question if you’re deep into a conversation about the topic, like interacting with literature and science journals. AI will not capture that human element,” he said.

Jones also strongly rejects the idea that generative AI will take away a human’s ability to think and use brain power. “If by ‘thinking’ we mean the generative idea, the new perspective on something—AI won’t stop that at all. It would open more doors,” he explained.

“Overall, I am optimistic, but I do think we have to work with students about what we mean when we ask, ‘is this your work, are these your ideas, is this your argument?’” Jones added.

“Technology evolution is exponential,” said Edelstein. “Timelines of technological development are going to become more and more compressed. Where we’d see a jump every 100 years, became every 50 years, and now every 5 years. That is only going to accelerate.”

That acceleration will likely take the use of generative AI beyond the traditional classroom and into the supplemental instruction, special education and college classrooms. Cheryl Angeloff, a Title I Coordinator at St. Christine and St. Nicholas elementary schools, said she believes teachers can harness the power of AI to reach students who learn differently: “AI has its place, but especially with kids with disabilities, I definitely say it can benefit the students.”

Angeloff explained that the more information teachers and administrators have about how AI can aid teaching, the better. “AI can be used in the supplemental instruction classroom, but you need to have the right people to design the program to incorporate AI into that kind of learning environment,” she said.

Several colleges in Ohio embrace this new technology, and Walsh University is among those pioneering the use of AI in higher education. Walsh hopes to teach students how to use AI in ways that align with its core values, such as ethics and respect.

Walsh faculty and staff believe the best place to begin teaching these concepts is in the K-12 classroom, which led them to develop its Unleashing the Power of AI: Empowering Educators Everywhere professional development course. This course provides K-12 teachers and staff with AI insights and hands-on experiences that they can take to their own classrooms and institutions.

Like Angeloff, Walsh’s chair of Mathematics and Science Neil Walsh, shares in the belief that a solidly built AI program is the key to student success, and this is what Walsh hopes to achieve by offering its AI professional development course. “We want to provide the tools and the framework for educators to bring AI into their classrooms in ways that reflect the core values of a Catholic education,” he said.

From the Catholic kindergarten to college, and from business to art to writing classrooms, the mission of Diocese of Youngstown Catholic schools is to “provide students with an educational experience that nurtures faith, inspires learning, fosters service and builds leadership building the Kingdom of God.” With the structure the Catholic classroom provides, coupled with the technological ambition of teachers and administrators, students of diocesan schools are well-positioned to use generative AI in a way that benefits themselves and others.