Cremation is an increasingly used option for families burying a loved one. The Catholic Church allows for that option but has provisions to ensure respectful treatment for the deceased.

“More people are using cremation today,” said Humility of Mary Sister Pat Fessler, a former chaplain at St. Elizabeth Hospital, Youngstown, grief support specialist for Higgins Reardon Funeral Homes, which serves families in Mahoning and Columbia counties, and a pastoral assistant at Zion Lutheran Church, Youngstown.

Burial cost is a prime reason, Sister Pat said.

“More and more deceased bodies will be cremated, and that trend will continue to grow,” with 50 percent or more now opting for cremation, noted Mike Irwin, a funeral director at Augustine Funeral Home, Youngstown. Irwin is also music director at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Parish in McDonald and a retired veteran with 30 years of service at the Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities.

The Church allows for cremation when it is rightly understood and practiced, while also offering caution—noting that traditional burial is the Church’s preferred method, and measures must be taken to ensure the cremated remains of a deceased human being are treated with the proper respect.

Christa Blasko, diocesan director of cemeteries, cited confusion among many Catholics on the issue of cremation.

“A lot of Catholics are unaware of the Church’s teaching,” either lacking awareness that the Church allows it, or, conversely, lacking the proper comprehension of the Church’s perception on the proper final disposition of cremated remains, Blasko explained. Such improper disposition includes keeping cremated remains in a family’s home or scattering them in a place that held special significance for the loved ones—such as a lake or park.

“We have to educate people,” Blasko notes.

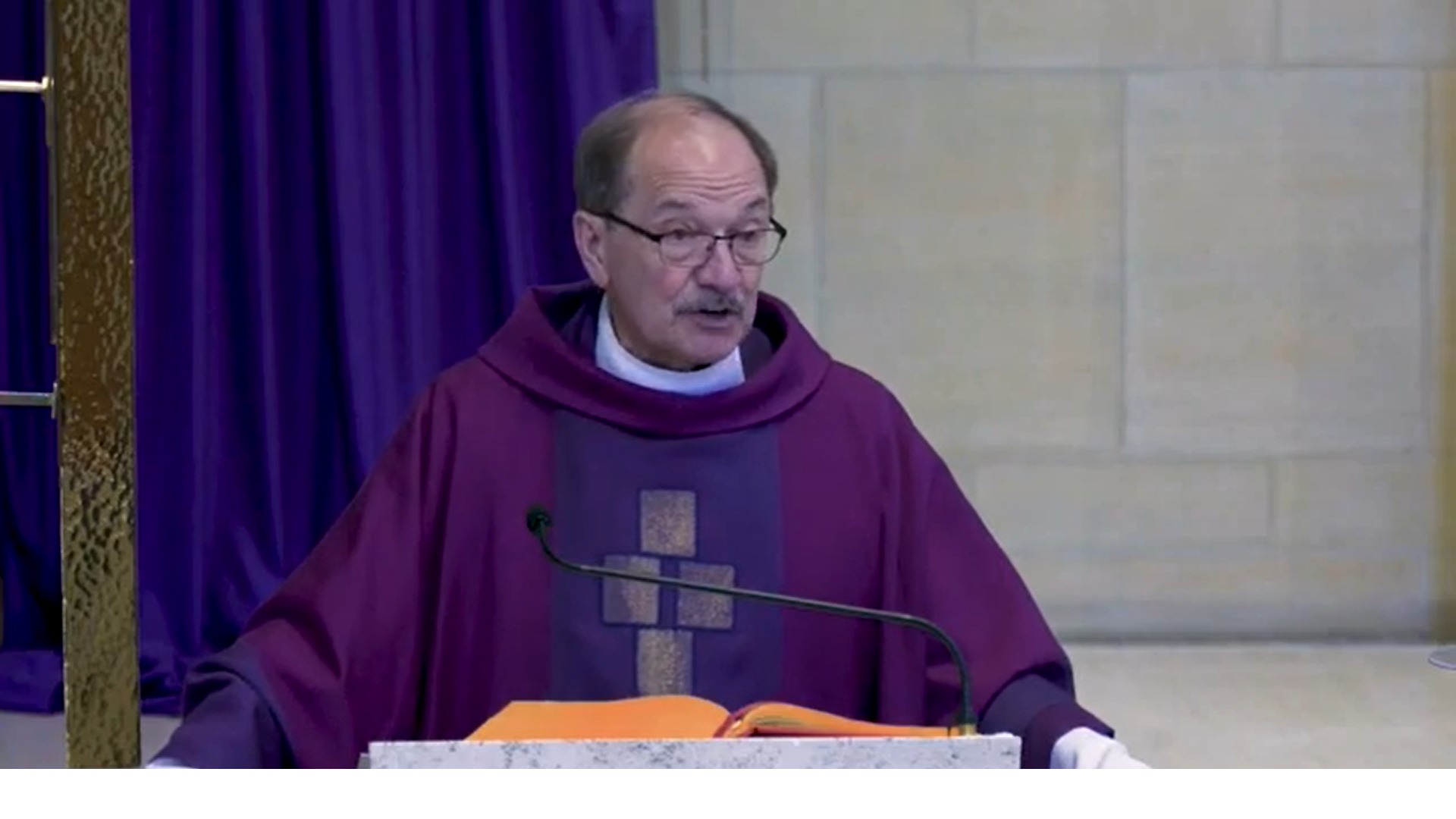

“Prompted by respect for the human body and a deep faith in the resurrection of Christ through the centuries, the Church has encouraged burial of the bodies of the dead after the manner of Christ’s own burial,” said Father Michael Balash, director of the diocesan Office of Worship.

Yet, “the Church made the concession” in 1963, allowing for cremation for Catholics seeking a Catholic funeral and burial for their loves ones, or in planning for their funeral and burial, Father Balash said. Traditional burial, however, is still the preferred option.

“It is common practice to encourage burying the body of the deceased, since the presence of the body better expresses the values which the Church affirms in the funeral rites”—specifically the Christian belief in resurrection of the body and the dignity of the human person, Father Balash continued.

“The concession for cremation comes with the understanding that the remains are treated with the same dignity and reverence” as a body not cremated.

To ensure that sense of reverence, the Church calls for burial or interment of the cremated remains of the deceased in such a setting as a grave or mausoleum, Father Balash continued.

Monsignor John Zuraw, diocesan vicar general, who wrote his thesis, “Ecclesiastical Funeral Rites: A Change in Law and Perspective,” for his licentiate in canon law at the Catholic University of America, explains that the Christian tradition of burying the body of the deceased has deep roots.

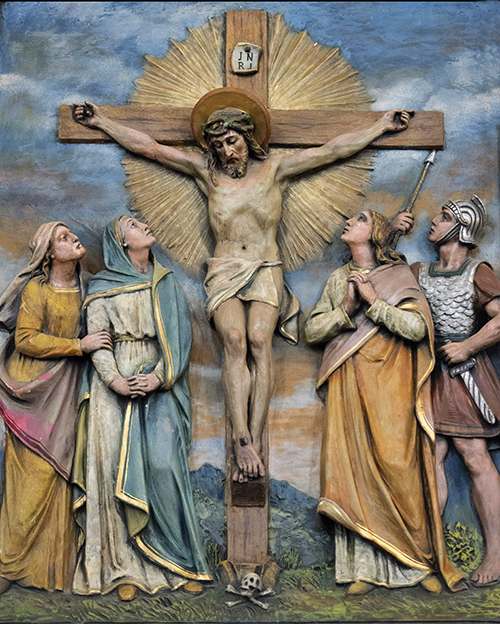

“From the beginning, Christians practiced earth burial and not cremation,” imitating the burial of Christ and following Jewish tradition, Monsignor Zuraw pointed out. “There was an intrinsic link between earth burial and the resurrection” reflecting the pascal mystery—involving the suffering, death, resurrection, ascension and glorification of Christ.

“The catacombs and bodily relics of the saints and martyrs gave evidence of the dignified burial rites of the early Christians, even though cremation was practiced in ancient pagan Rome,” Monsignor Zuraw explained. “Under the Holy Roman Emperors, cremation all but disappeared.”

When a revival in cremation occurred across Europe in the 19th century, Monsignor Zuraw said, the Church forcefully addressed the issue. Though cremation was initially promoted for reasons of hygiene and scientific progress, the forces of anti-clericalism seized upon the practice to promote an anti-religious, materialist agenda. In response, the Vatican in 1886 issued directives against Catholics practicing cremation, emphasizing the un-Christian motivation of many cremation advocates and concern that the practice clashed with the liturgical rites of Christian burial.

The Church went further, incorporating prohibition of cremation into the 1917 Code of Canon Law and denying Christian burial to those who were cremated. In 1926, the Vatican’s Holy Office underscored its opposition to cremation as not only an attempt to de-emphasize the resurrection of the body, but even to undermine natural respect for the bodies of the deceased.

As the 20th century progressed, however, the Church began reflecting on certain practices and theological understanding—as seen most clearly in the convening of the Second Vatican Council from 1962 to 1965. In that spirit, the Church also gave renewed consideration to the issue of cremation.

In 1963, the Vatican’s Holy Office, now known as the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, issued an instruction, Piam et Constantem (“Pious and Constant”), addressing cremation.

“As Church leaders were examining other issues, the Church also considered cremation, examining the subject matter and getting a clearer understanding of what was going on in the whole world,” Monsignor Zuraw explained. For example, there were parts of the world where the availability of land for burial was and is an issue along with considerations of hygienic practices. “So the Holy Office adopted a more pastoral approach to cremation.”

The instruction noted that the Church’s objection to cremation arose from certain advocates who used cremation as “a symbol of their antagonistic denial of Christian dogma,” specifically denial of “the resurrection of the dead and the immortality of the soul. Such an intent,” was not “inherent in the meaning of cremation itself.”

In light of attitudinal change in recent years and “more frequent and clearer situations impeding the practice of burial,” the instruction notes, the Vatican had received “repeated requests for a relaxation of Church disciplines relative to cremation.” The procedure was clearly being advocated, according to the document, not out of hatred of the Church or Christian customs, “but rather for reasons of health, economics, or other reasons involving private or public order.”

Therefore, the Holy See instructed the bishops of the world “to relax somewhat the prescriptions of canon law touching on cremation,” allowing the practice and not denying Christian burial to those whose bodies were cremated, as long as it was clear that the reason for choosing cremation was neither “a denial of Christian dogmas, the animosity of a secret society or hatred of the Catholic religion and the Church.” Burial would continue to be the preferred method, but cremation would be allowed in cases of genuine need and all necessary measures would need to be taken “to preserve the practice of reverently burying the faithful departed.”

Subsequent Church directives, including the Vatican Congregation for Divine Worship’s 1969 Ordo Exsequiarum (which implemented the reforms of the Second Vatican Council), the 1983 Code of Canon Law and the U.S. bishops 1997 Order of Christian Funerals reaffirmed the allowance for cremation with the proper understanding of the circumstances, and the Church’s preference for traditional burial. The Order of Christian Funerals also called for the presence of the cremated remains in the church at the funeral Mass (unless cremation takes place following the funeral).

The Order of Christian Funerals also declares: “The cremated remains of a body should be treated with the same respect given to the human body from which they come. This includes the use of a worthy vessel to contain the ashes, the manner in which they are carried and the care and attention to appropriate placement and transport, and the final disposition. The cremated remains should be buried in a grave or entombed in a mausoleum or columbarium. The practice of scattering cremated remains on the sea, from the air, or on the ground, or keeping cremated remains in the home of a relative or friend of the deceased are not the reverent disposition that the Church requires.”

In a 2012 newsletter, the U.S. bishops’ Committee on Divine Worship also called for the Church to offer assistance for families who chose cremation to ensure that they be able to secure “reverent burial for the cremated remains of the deceased.”

In light of the increasing numbers of Catholics who choose cremation, Father Balash explained, in 2016 the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (now known as the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith) published updated guidelines for Catholics regarding cremation. The instruction Ad resurgendum cum Christo (“To Rise With Christ”), restated the original guidelines and directives for cremation, emphasizing in particular the obligation of Catholics to properly entomb cremated remains.

When dealing with families who embrace improper burial practices, Father Balash said, “the pastoral thing to do is to try to make them aware of what the cremated remains are”—their significance and the reverence due to them as the remains of human beings created in the image and likeness of God. When that is explained, Father Balash said, “most people get it.”

Irwin, from his experiences both in parish ministry and as a funeral director, is aware of the difficulties with families who, understandably he said, choose to hang on to cremated remains of loved ones.

“It is a legitimate concern,” said Irwin, who noted that much of the work of funeral directors is focused on the families as well as the deceased persons themselves—“to walk with the families in this journey, to help them get to where they need to be.“

His concern about families holding on to cremated remains is that “there is a danger that you have not fully let go of the person you lost. Part of being a Catholic is letting go of excessive attachments so that we can go forward—to see that death is not the end, but the beginning, or as said in the liturgy: ‘Life is not ended but merely changed.’” Rather than holding onto the cremated remains, he suggested “focusing on prayer for the deceased person—to let go and give that person to God.”

He also noted that some families have left cremated remains at the funeral home, posing a dilemma for funeral directors. He expressed gratitude to the diocesan Christian Funeral and Cemetery Services for their efforts to provide fitting interment for such cremated remains.

Among the many ways that the diocesan Christian Funeral and Cemetery Services seeks to serve, Blasko said, is assisting families who have cremated remains of their loved ones.

“We have an All Souls Remembrance service, when we ask everyone who has cremated remains to bring the cremated remains to one of our cemeteries,” she explained, so that the cemetery can place the remains “in a sacred space at zero cost. And we do this for people of all faiths. This is the place for their remains to be.”

“We have many options for families and are willing to work with them according to their needs,” Blasko said.