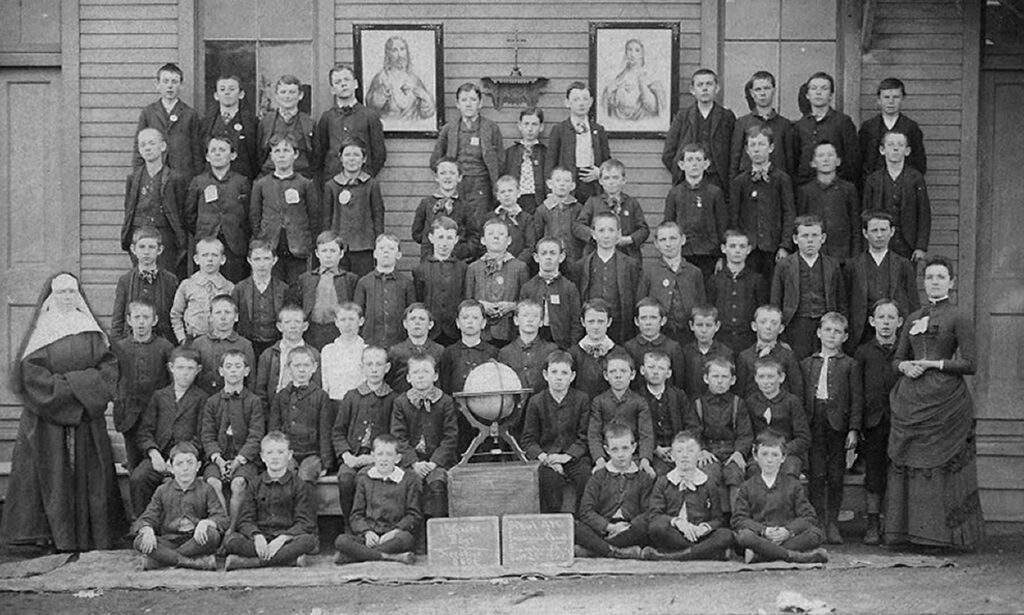

When six Ursuline sisters stepped off a train at Youngstown’s Erie Terminal in September 1874, they encountered a smoky industrial town that was still reeling from the effects of a recent economic downturn. Despite this inauspicious beginning, the Ursuline Sisters of Youngstown would go on to staff more than a dozen area parochial schools, while organizing the city’s first Catholic high school.

Today, the religious community is preparing to mark 150 years of ministry in the Mahoning Valley on September 18, 2024. As they count down to this significant milestone, the Ursuline Sisters will commemorate their long presence in the area with a series of events starting in September 2023.

As part of this yearlong celebration, the religious community has commissioned a book that will explore their rich history. The 200-page book, titled The Ursulines Sisters of Youngstown: Serving the Mahoning Valley Since 1874, is scheduled to be released in 2024 by the Charleston-based History Press.

Sister Mary McCormick, general superior of the Ursuline Sisters of Youngstown, stressed the importance of honoring the community’s past. “First and foremost, the Ursuline Sisters are disciples of Jesus and women who have taken seriously His last words: ‘Go therefore and make disciples of all nations,’” she said.

“When the Ursulines arrived in Youngstown in 1874, they took up that task, and they have been doing so in the greater Youngstown area ever since.”

Sister Mary noted that over the years, the order’s growth has mirrored the development of the surrounding community. Starting in the early 20th century, the growth of the local steel industry had a major impact on the city’s population, which rose from 33,220 to 44,885 between 1890 and 1900—an increase of more than 11,000 residents. Moreover, the population was on track to exceed 100,000 within a couple of decades.

Nowhere was the city’s development more evident than in the short block of Elm Street that ran north from Wood Street to West Rayen Avenue. In the early 1900s, the second edifice of St. Columba’s Church was still standing at the southern end of Elm Street, although it functioned mainly as the parish school’s gymnasium. Deconsecrated after a final Mass held in June 1903, the modest brick structure gave way to the parish’s third edifice: a huge granite neo-Gothic structure with square towers that straddled a rose window glazed with stained glass.

During this period, the Ursuline sisters, who staffed St. Columba’s parish school, benefited from a dramatic expansion of their educational mission. By September 1905, the religious community had opened Ursuline Academy, the forerunner of Ursuline High School.

In April 1925, the new building of Ursuline Academy, located on a stretch of the campus near Bryson Street, opened for classes. Five years later, in 1930, Cleveland Archbishop Joseph Schrembs recommended that the religious community turn the academy into a co-ed institution. At that point, Ursuline Academy became known officially as Ursuline High School.

By that time, the Ursuline Sisters were firmly established as religious educators. Between the early 1880s and late 1920s, the Ursulines had opened no less than 11 parish schools, including St. Columba, St. Ann, Immaculate Conception, Saints Cyril and Methodius, St. Rose (Girard), Saints Peter and Paul, Sacred Heart of Jesus, St. John the Baptist (Campbell), St. Charles Borromeo (Boardman), and St. Nicholas (Struthers).

Then, in September 1944, less than a year after the establishment of the Diocese of Youngstown, the Ursulines reopened Youngstown’s St. Patrick’s Elementary School on the south side. (The parish school was previously staffed by the Cleveland-based Sisters of St. Joseph.)

The expansion of the Ursulines’ educational ministry reflected the growth of the region. On June 4, 1943, an area of northeast Ohio—including Stark, Columbiana, Mahoning, Portage, Trumbull and Ashtabula counties—was canonically established as the Diocese of Youngstown. The new diocese, which comprised 3,404 square miles, featured several major manufacturing and steel-production centers as well as large stretches of agricultural territory.

In the wake of a devastating fire that destroyed the first edifice of St. Columba Cathedral in 1954, the new diocese continued to witness exponential growth. That same year, Ursuline High School was expanded under diocesan control. Meanwhile, Youngstown’s Bishop Emmet Walsh dedicated the new physical plant of Cardinal Mooney High School, a move that reflected widespread optimism about the future of the Diocese of Youngstown.

In 1959, parish enrollment in Youngstown and surrounding Mahoning County reached an all-time high, with 16,914 enrolled. Two years later, in 1961, a Youngstown school board estimate indicated that 13,318 students were enrolled in Catholic schools—elementary and secondary—while 27,324 attended public schools. In short, about one-third of the city’s school-age population was enrolled in Catholic schools.

Hence, by the early 1960s, the Ursuline Sisters of Youngstown were a major force within the Mahoning Valley. On May 24, 1964, Bishop Walsh presided over the dedication of the religious community’s new Motherhouse, a $1.2-million complex in the suburb of Canfield.

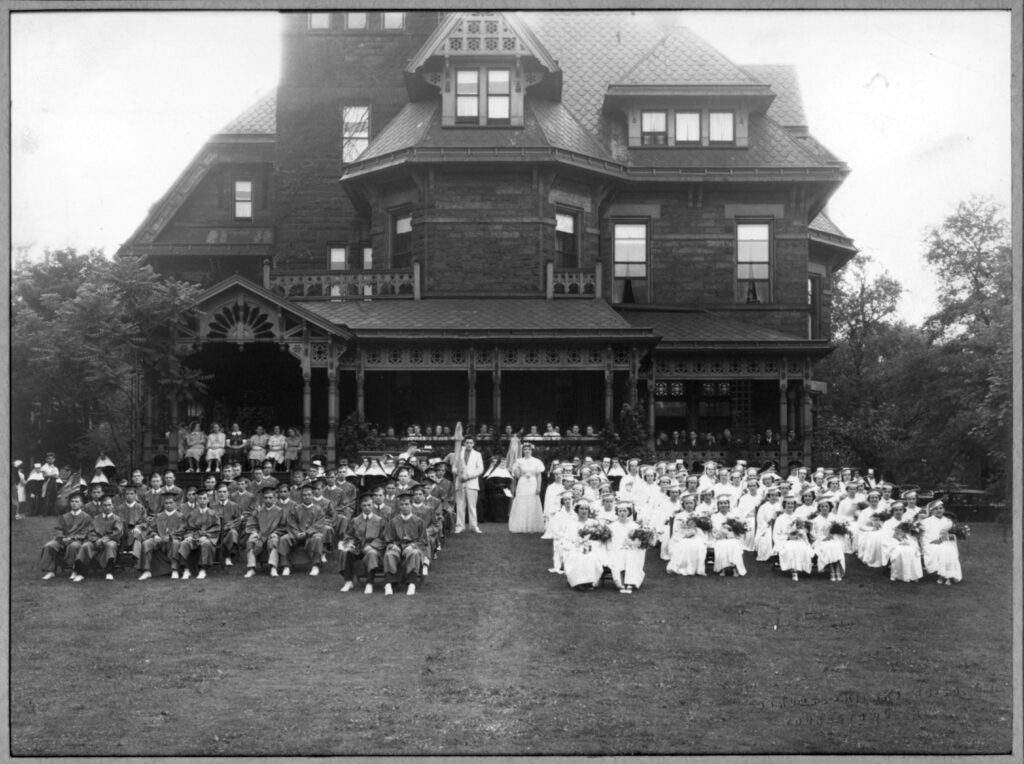

The media informed readers that the modern, two-story structure could accommodate 115 sisters and students, some of whom were being relocated from two older facilities: a late 19th-century brick convent, located just north of downtown Youngstown, and the former Motherhouse in nearby Liberty Township, which once served as the private residence of an industrial baron.

From all appearances, the Ursuline Sisters had embarked on an exciting new chapter of their journey, one that was bound to involve the continuous growth of their numbers and infrastructure.

Yet, in the six decades since the opening of the Ursuline Motherhouse, the religious community has been utterly transformed, along with the surrounding metropolitan area. Built in the early 1960s to accommodate more than 100 residents, the Motherhouse today serves fewer than 30 sisters, while the onetime industrial center of Youngstown, whose population peaked at 170,000, now hosts fewer than 40,000 individuals.

That said, the story of the Ursuline Sisters of Youngstown is scarcely a narrative of entropy and decline. Like scores of religious communities throughout the Northeastern United States, the Ursulines have struggled to address difficulties arising from declining vocations, deindustrialization, depopulation, and chronic economic inequality.

In response to this array of challenges, the Ursulines have drawn upon the example of their founder, Saint Angela Merici, who envisioned members of her order as beacons of Christian values who would assist in the revitalization of a weakened and divided Church, explained Sister Patricia McNicholas, a member of the community’s leadership team.

Widely regarded as a force for good within the larger community, the Ursuline Sisters have shown a commitment to the poor that has involved strategic partnerships with members of the laity. Respected for their earlier contributions as classroom educators, today’s Ursulines take no less pride in ministries that benefit those at the margins of society.

The religious community’s programs for single mothers, including Beatitude House, call to mind Saint Angela’s determination to assist women who had been exploited by the military occupiers of Brescia in 16th-century Italy. In the same vein, the Ursulines’ work with those affected by HIV/AIDS echoes Saint Angela’s well-known compassion for those suffering from syphilis, who were then stigmatized and denied admission to conventional hospitals.

The Ursuline community’s decision, in more recent decades, to sell off acres of land and reuse portions of their physical plant to benefit their ministries, seems especially consistent with their founder’s intentions.

As Sister Patricia observed, Saint Angela envisioned her order as a loose network of laypeople who would help to reform a struggling Church. Indeed, there is no reason to suspect that she anticipated the tertiary order’s transformation into a cloistered religious community.

“If you look at the early history of the Ursulines, they weren’t even a religious community,” Sister Patricia noted. “It was only after the Council of Trent, which occurred shortly after the founding of the Company of St. Ursula, that there was this pressure to cloister.” Once they were confined to convents, the Ursuline Sisters recognized that the education of young women was among the few ministries they could maintain.

The order’s present-day leaders discern striking parallels between the challenges Saint Angela faced and those confronting contemporary American Catholics. Now, as in her time, shrinking numbers of clergy and religious highlight a need for meaningful lay participation in a divided Church. Hence, the Ursuline Sisters’ efforts to address the needs of the present have brought them closer than ever to their spiritual foundations.

For Sister Mary, this story of faith is well worth preserving. “When you think of it, if it hadn’t been for His disciples telling the story of Jesus, no one would have ever heard of Him,” she noted. “The Church learned then how important it was to tell the story, so there would be a living memory of what He had done.”

She pointed out that sacred texts with a strong narrative element remain central to the faith of modern-day Christians and Jews. “Our Jewish ancestors in faith left lots of writings,” Sister Mary stated. “Only the disciples of Jesus left those writings. But they left a living memory. That’s why we want to celebrate this anniversary. The women of the late century established a foundation on which we build. They were strong, faithful women who engaged in the lives of the people around them—we continue that.”